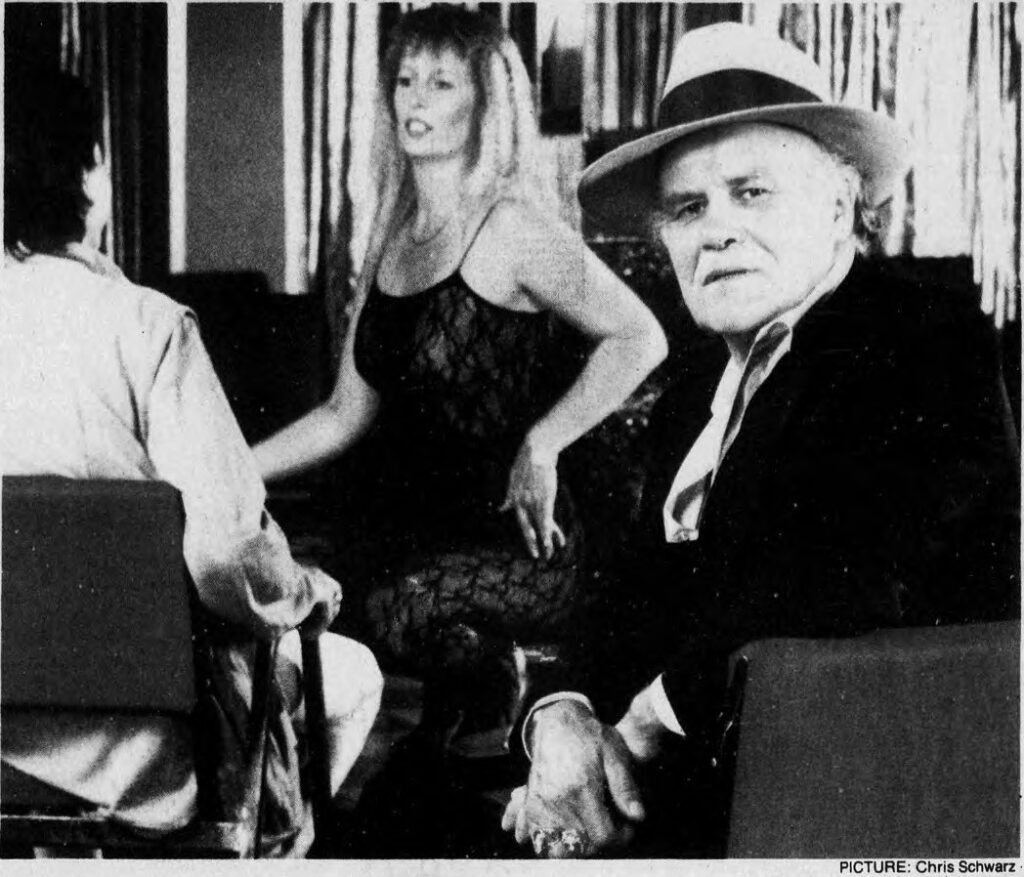

Sex and Sin in the City of Champions: The Story of Chez Pierre

In a quiet corner of downtown Edmonton, some of the city’s oldest businesses and institutions endure. A dry-cleaning business has occupied a building at Jasper Avenue and 105th Street since the 1930s. Footage from a tourist’s idyllic visit in 1977 captures its bygone neon sign under the former name Expert Cleaners.i

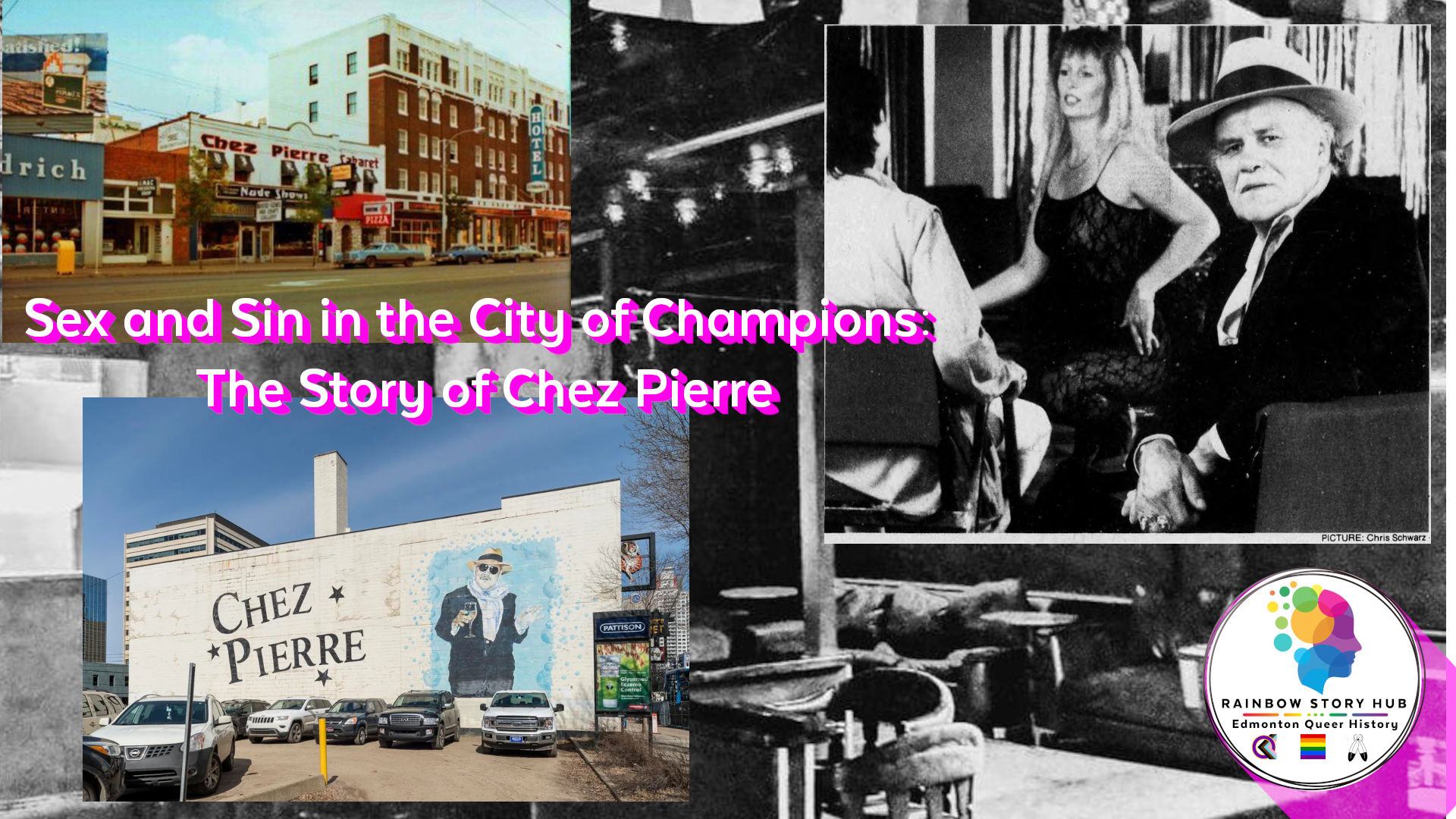

Nearby, just steps from the former Flash gay nightclub, is Chez Pierre, Western Canada’s longest continually operating strip club, founded in 1970 by “exotic entertainment pioneer” Pierre Cochard.ii

Today, when the marquee lights are off, only a sandwich board advertising tacos and a mural of the late Cochard signal its presence, but in its early years, the club had more attention than it knew what to do with. Alongside legal conflicts surrounding censorship and obscenity, it clashed with the First Presbyterian Church across the street—a still-active congregation founded in 1912—and met the ire of many faith leaders.

Cochard was born in Belgium in 1925 and moved to Canada in 1951 with his first wife, Maithe.iii He started Chuckwagon Catering in Edmonton with his friend Henri but later sold his shares, moving back to Belgium with Maithe and their two children.iv Cochard’s ambition of opening a bar in Spain did not pan out.v He and his family moved back to Alberta, this time settling in Grande Prairie, where Cochard ran a club called the Green Door.vi

He later came back to Edmonton, where he opened the city’s first strip club, Pegasusvii—a safe haven for the queer community, including drag queens.viii Today, Edmontonians can see drag shows at Evolution Wonderlounge and at events across the city, but in the early 1970s, drag was truly underground. As Ron Byers and Rob Browatzke write, Cochard hired two drag queens to perform at Pegasus in 1971, which was “a straight business.”ix Millie (Paul Chisholm) and Chatty Cathy (Duane Shave) performed Edmonton’s first “public drag show.”x

Chez Pierre opened the same year at 10613 Jasper Avenue, down the street from Pegasus, which closed sometime before 1974. It quickly saw legal trouble. In 1972, Darlene Campbell, a dancer at Chez Pierre and Cochard’s partner-turned-wife, was convicted of immoral theatrical performance for her work at the club.xi The Criminal Code of Canada states: “Everyone commits an offence who takes part or appears as an actor, performer, or assistant in any capacity, in an immoral, indecent or obscene performance, entertainment or representation in a theatre.”xii She argued in court that Chez Pierre was not legally a theatre and believed “bottomless dancing” was permitted under a Supreme Court ruling.xiii

At appeal, Justice Kerans wrote that at “the start of [Campbell’s] performance, she was wearing some clothes. By the end of her performance, she was not wearing any clothes.”xiv Indeed, Kerans had “no doubt in coming to the conclusion that [Campbell’s performance fell] within the meaning of the section, and that, in doing what she did, the appellant took part as a performer.”xv

While Kerans was convinced that Campbell’s dance was immoral and that Chez Pierre was indeed a theatre, he did not believe she possessed the mens rea to register a conviction, meaning she did not have the necessary guilty mind or intent required for criminal responsibility. In closing, he stated, “I am not aware that these tawdry nude night-club acts […] have become a prevalent problem in our community. Therefore, I think, out of [a] sense of justice, [but] certainly not out of any sense of approval for what this lady did, it would be appropriate for me to grant her an absolute discharge, and that is what I do.”xvi

In other words, Justice Kerans found Campbell guilty, but no formal conviction was entered. Despite this minor success, performers at Chez Pierre continued to face criminal prosecution, including drag queens and male strippers.

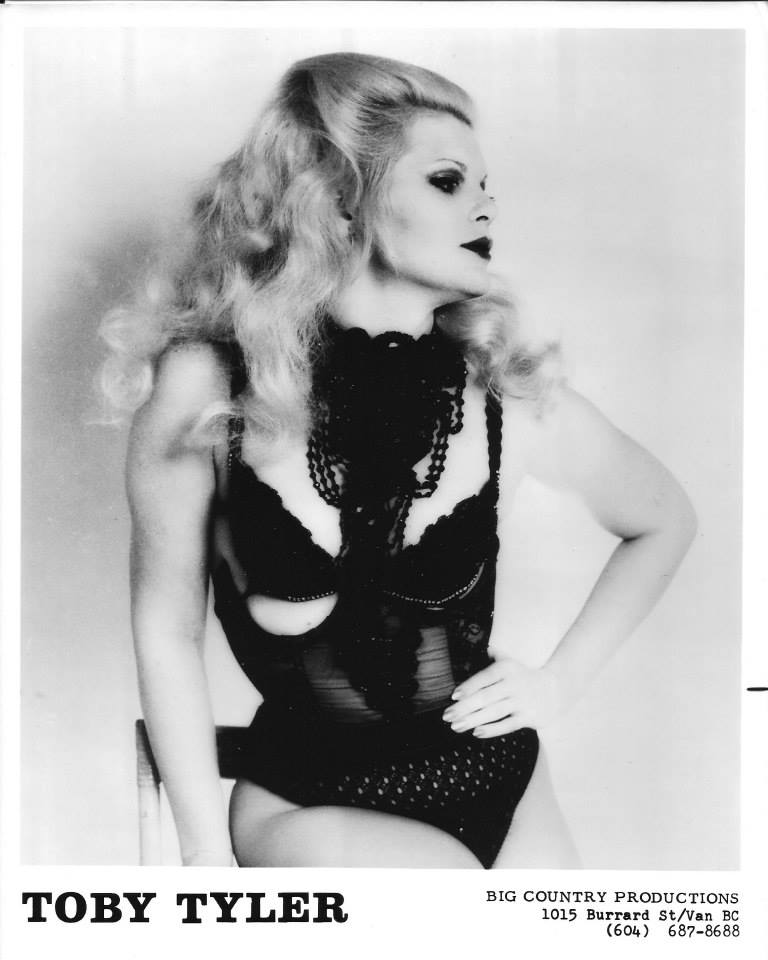

In 1975, Richard Graham (who performed under the names Diane Ricci and Toby Tyler) and Donald Hewitt, also known as Justin Ames, were arrested for immoral theatrical performance for their controversial “Mirabella” show.xvii They were found guilty after two separate trials.

At the Supreme Court of Alberta Appellate Division—renamed the Alberta Court of Appeal in 1979—The Honourable Mr. Justice Clement described Graham and Hewitt’s performance: they “caressed erotically,” “progressively removed each other’s clothing,” “assumed animal like positions,” and “simulated an act of intercourse.”xviii He dismissed the appeal, stating that the second trial judge correctly found the performance “obscene by the community standards it was his duty to determine and uphold.”xix In fact, Clement “would have been surprised if he had come to any other conclusion.”xx

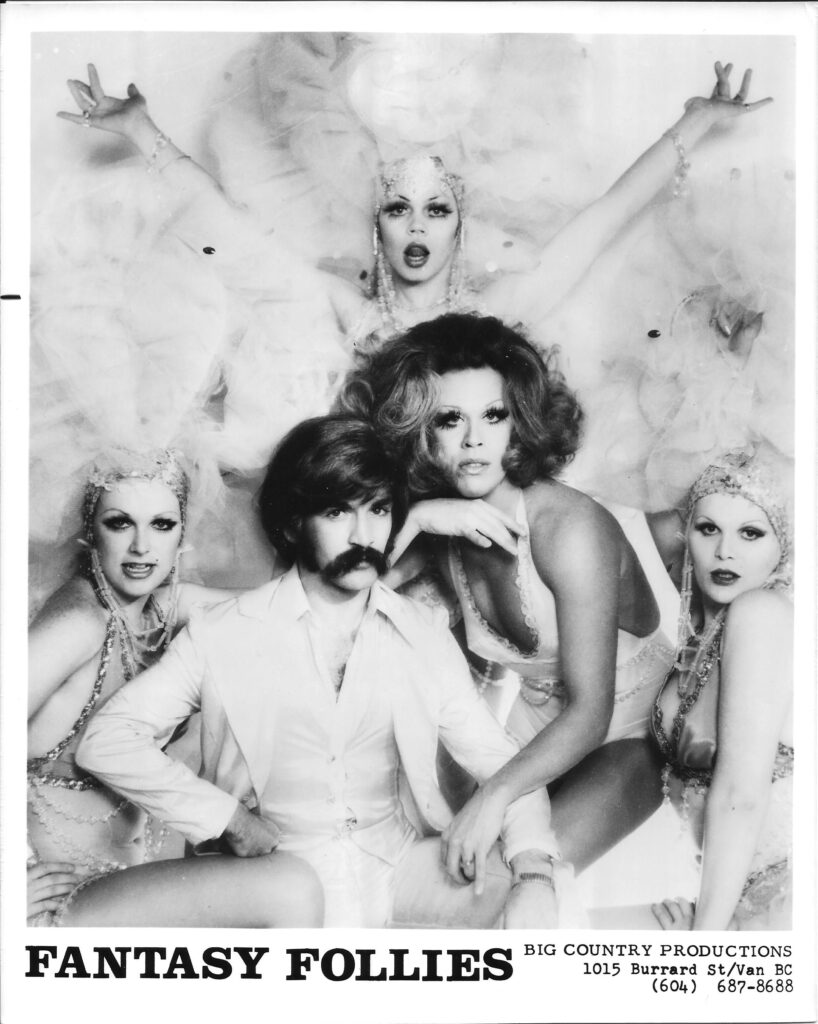

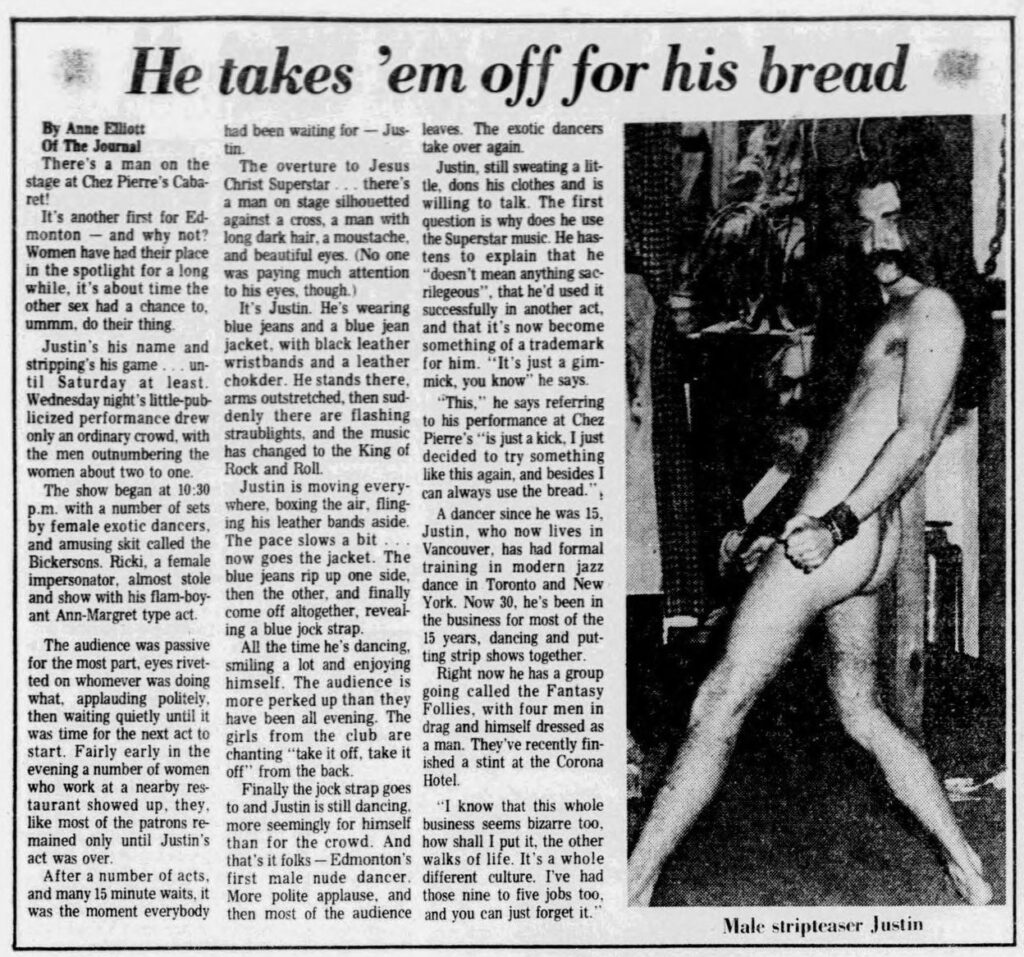

Curiously, Hewitt (as Ames) had already been performing all over Edmonton and across Canada as an exotic dancer and along with the female impersonator group Fantasy Follies. Months before his arrest, Hewitt was featured in a cheeky Edmonton Journal article as “Edmonton’s first male nude dancer.”xxi

In 1979, Christian conservative Eddie Keehn, who had run unsuccessfully for mayor of Edmonton two years earlier, announced an anti-pornography march through the city’s downtown that was to end at Chez Pierre, which he saw as an emblem of sin and depravity.xxii In fact, Keehn promised to “board up” the door to Chez Pierre to prevent entry into the establishment.xxiii Yet, Keehn never showed up.

Along with a few family members and supporters, he instead stood in front of Mike’s News on Jasper Avenue, promising to march again if his “anti-smut campaign” garnered more support.xxiv Keehn was a known homophobe. He “called for the firing of gay and lesbian city employees during the [mayoral] campaign, as well as the closure of gay clubs” and sensationalized the 1981 gross indecency case against Elaine Kuresh, which led to her suicide.xxv

By late 1980, Cochard had plans to relocate Chez Pierre within downtown Edmonton, setting his sights on 10040 105th Street. It was a risky move. Across the street, W.H. Lawrence, a “representative of the 600-member congregation of First Presbyterian Church,” complained to city council’s development appeal board, arguing that “titillated customers of a strip joint are easy marks for pimps and prostitutes.”xxvi

10040 105 St NW, Edmonton

Down the street, Expert Cleaners were also not thrilled about Cochard’s move. Ultimately, however, Cochard won the battle as the board “rejected opposition from numerous groups and upheld the issuing of a permit to Chez Pierre’s Cabaret.”xxvii

This was not Cochard’s first rodeo with religious leaders. In addition to Keehn, evangelist Max Solbrekken criticized Cochard in the press. In August 1980, Cochard surprised Solbrekken by picketing outside his CJCA phone-in talk show interview, where Solbrekken said he wanted to see Chez Pierre closed.xxviii Cochard held a sign reading, “Free Love is No Pornography, Max,” before being invited on air to debate Solbrekken, who called Cochard’s customers “slobbering drunks,” despite Chez Pierre lacking a liquor license.xxix

Although Cochard’s victories against religious figures and other moralists are impressive feats, the wider backdrop of sex and moral panic in Edmonton in the early 1980s would seem to eclipse them. In January 1980, the Jasper Cinema in the far northwest of the city saw its copy of the pornographic horror comedy Dracula Sucks (1978) confiscated under obscenity laws.xxx Its sister theatre, the Towne Cinema, had the same thing happen with Caligula (1979) in 1981.xxxi

That year, police raided the Pisces Health Spa, a gay bathhouse, leading to dozens of arrests.xxxii Violent homophobes patrolled cruising grounds near Bellamy Hill and beat up gay men, or at least threatened to.xxxiii

Yet, Cochard steadfastly defended queer people, believing that Chez Pierre should be a safe space for sexual dissidents. He famously said, “Strippers are God’s children too.”xxxiv Thanks to Cochard’s “unfaltering acceptance,” Chez Pierre “remains a welcoming home for Edmonton’s drag scene to this day,”xxxv just over one year since Cochard’s death at age 98.

Notes:

i “1977 – Edmonton – Alberta – Canada – North America – 8mm – 1970s – Kanada – City – Super 8,” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XFSA5QS3cPo.

ii Darcy Ropchan, “Family of Edmonton Exotic Entertainment Pioneer Pierre Cochard Remembers His Legacy,” CityNews, last modified September 26, 2023, https://edmonton.citynews.ca/2023/09/26/edmonton-exotic-entertainment-pioneer-pierre-cochard/.

iii Obituary of Pierre Cochard, Edmonton Journal, https://edmontonjournal.remembering.ca/obituary/pierre-cochard-1088931145.

iv Ibid.

v Ibid.

vi Ibid.

vii Ibid.

viii Ron Byers and Rob Browatzke, “History of Edmonton’s Gay Bars, Part 3: The Long-Running,” Edmonton City as Museum Project, last modified October 2, 2020, https://citymuseumedmonton.ca/2020/10/02/history-of-edmontons-gay-bars-part-3-the-long-running/.

ix Ibid.

x Ibid.

xi R. v. Campbell, 1972 CanLII 1395 (AB KB), https://canlii.ca/t/gb11f>, retrieved on 2024-10-18.

xii https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-46/section-167.html

xiii R. v. Campbell.

xiv Ibid.

xv Ibid.

xvi Ibid.

xvii R. v. Graham, 1977 ALTASCAD 90 (CanLII), <https://canlii.ca/t/fp3b7>, retrieved on 2024-10-17.

xviii Ibid.

xix Ibid.

xx Ibid.

xxi Anne Elliott, “He Takes ‘Em Off for His Bread,” Edmonton Journal, May 15, 1975, pg. 3.

xxii “Anti-Porno March Goes Nowhere,” Edmonton Journal, March 23, 1979, pg. 22.

xxiii Ibid.

xxiv Ibid.

xxv “Eddie Keehn,” Prosopography: Lesbian and Gay Liberation in Canada, https://prosopography.lglc.ca/person/eddie-keehn/. For more on the Kuresh case, see Chris Bearchell, “Gross Indecency Laws Claim Another Life,” The Body Politic 75 (1981): pg. 15.

xxvi Barb Livingstone, “Pierre’s Plans Bring Protest,” Edmonton Journal, January 9, 1981, pg. 15.

xxvii “Shops, Churches Lose; Bump and Grind Wins,” Edmonton Journal, January 16, 1981, pg. 16.

xxviii Chris Dornan, “Pierre Can’t Convince Pastor Max to Join Him on the Way of All Flesh,” Edmonton Journal, August 15, 1980, pg. 21.

xxix Ibid.

xxx Towne Cinema Theatres, Ltd. v. The Queen, 1985 1 SCR 494, https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/49/index.do.

xxxi Tom Barrett, “Caligula Confiscation Cost High,” Edmonton Journal, October 13, 1981, pg. 21.

xxxii Valerie J. Korinek, Prairie Fairies: A History of Queer Communities and People in Western Canada, 1930-1985 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018), 378.

xxxiii Ibid.

xxxiv Ropchan.

xxxv Byers and Browatzke.

Spread the word! Share this story now

36Shares

Advertisements