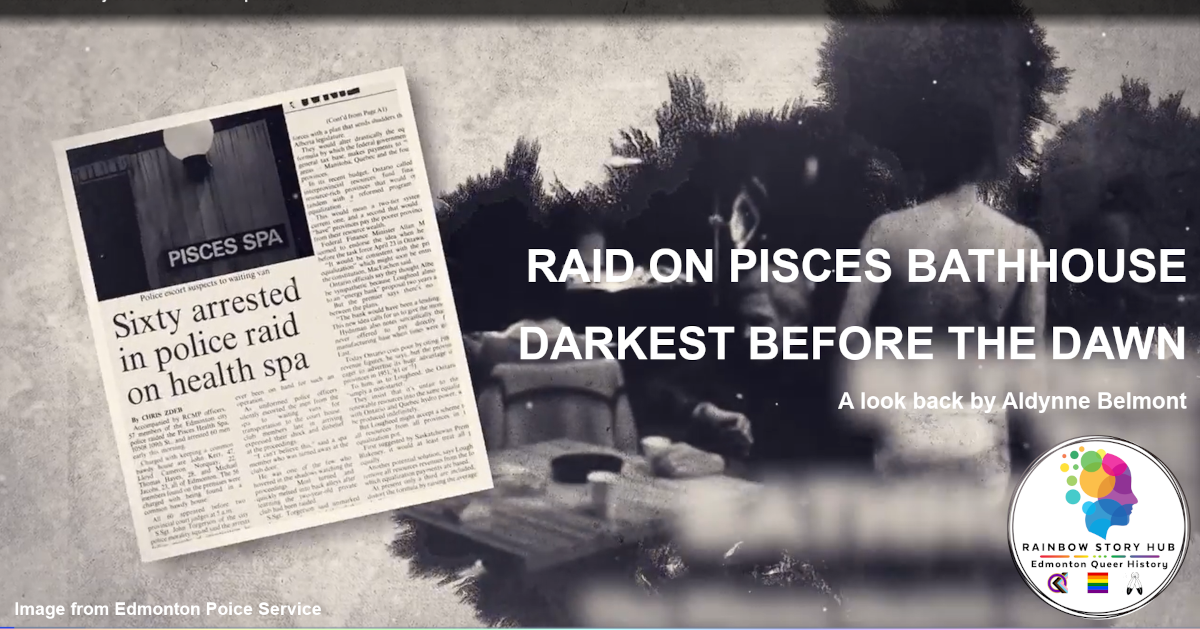

Raid on Pisces Bathhouse — Darkest Before the Dawn

I am sometimes embarrassed by the gaps in my queer knowledge. While I wouldn’t call myself completely naive, much less a prude, once in a while something leaps to the front of my vision and makes me aware of just how much I don’t know — I thought “cruising” was a synonym for the Southern slang “wheeling” until last year, and for the longest time, anything I knew about bathhouses was taken from an action set-piece in the third Pirates of the Caribbean film.

Put simply, this is why I find the story of the 1981 Pisces Bathhouse Raid so important. It’s fascinating, it seems like such comparatively recent history, formed a large part of Edmonton’s queer interpersonal identity, and yet have rarely seen it mentioned by my younger peers, if they know the story at all. It was the spark that lit the fire of 40 years of activism in this fair city, but stays a footnote for the vast majority of queer people. This generational divide in knowledge isn’t just about the event itself, but also how different queer communities relate to their shared history.

It is 1978, and the Pisces Health Spa has opened in Edmonton, establishing itself as the premier gay bathhouse of the prairies. It wasn’t completely without precedent — its contemporaries included the Gemini Bathhouse which had “moved to a location on Jasper Avenue that had once been the home of Edmonton’s first gay disco, Flashback” — but it was notable for being the best. Managed by John Kerr — choreographer for the Flashback Follies drag show — the spa boasted over 2, 000 members at its peak.

Three years later and halfway across the country, the Toronto Police Force mounts ‘Operation Soap’, a coordinated raid on four bathhouses on the night of February 5th, 1981. The Club Baths, Romans II Health and Recreation Spa, Richmond Street Health Emporium and The Barracks are all smashed by police, resulting in the arrest of 20 owners and 286 found-ins under charges of involvement with a “common bawdy-house”. There had been other raids — “dozens…across Canada between 1969 and 1981” since homosexuality was decriminalized, but Operation Soap emboldened a national police culture looking for an excuse to escalate their harassment of the queer community.

The meticulous operation being developed in Edmonton was one such escalation. An adjacent business with a view of the Pisces’ back-alley entrance served as a surveillance hub where patrons were photographed, filmed, and their car license plates noted. A total of nine undercover police detectives were commissioned to infiltrate the Pisces spa proper, masquerading as patrons and taking extensive — often explicit; “almost pornographic in nature” — notes on the spa’s activities, particularly sexual interactions among patrons. “The focus of the investigation was the common areas such as the dark room, the steam room, and the jacuzzi, where group sex supposedly occurred. After the first detective who had volunteered for the operation completed his first visit, it became apparent that the detectives would be more effective if they were in pairs, so afterwards the detectives would arrive as couples, present their membership cards, and pay the cover charge, which allowed them the cover story of being partners meeting at the spa.”

The genesis of the operation was a complaint from a Fred Griffiths, a gay community member who was “disgusted by the goings-on at the bathhouse even though he had never been inside.” Evidently this sentiment wasn’t all that rare, before or after the Pisces heyday — newspaper reports on the opening of Jasper Ave’s Down Under bathhouse in 1998 show that even nearly 20 years after the raid, people (queer or otherwise) still stereotyped gay bathhouses as pseudo-biblical dens of sin, “frankly horrified by the thought that the bathhouse [represented the expression of] anonymous sex1”and stating that “sexually-based businesses degrade the quality of a neighbourhood, substantially devalue property values as well as threaten the well-being of our children… [there are] legitimate crime concerns associated with these kinds of businesses.2”

These kinds of sentiments certainly haven’t gone away, and even inside the present queer community, I’ve seen people genuinely bristle at the mention of the bathhouse experience. I don’t think it’s rooted in any kind of prudishness or judgment, at least not a conscious or deliberate kind, but it does indicate a type of divide. There’s a separation between those whose queer experience has been meaningfully impacted by boathouse-as-space, and those who have had their perceptions of what a gay bathhouse is formed by the cishet hegemony. I think there can often be an instinctive tendency to fear perspectives that differ from our own, but this is rooted in a kind of queer paranoia; an inability to accept that the queer community is vast and varied, or a stubborn refusal to learn from our history, or sometimes both. I’m not sure what exactly, specifically drove Fred Griffiths to inform on his own community, but I theorize it may have to do with ensuring his own safety. To insistence on being “one of the good ones” in an attempt to ensure your safety is something that still exists within schisms of the queer community; the need to cover your own ass —desperately (and incorrectly) thinking they’ll pass you over when they come to destroy the queers — is understandable, but not justifiable.

That being said, Griffiths was actually tapped as an official civilian informant as the investigation ramped up; his information provided the evidence needed to launch the operation proper. The undercover detectives were treated as regulars by the spa staff. In a particularly telling moment, a detective who had forgotten his membership card was reprimanded by an attendant who warned, “We don’t want what happened in Toronto to happen here,” — the national climate of pervasive anti-gay sentiment was not lost on the Pisces Staff, and one has to wonder if the prospect of a potential raid was a ‘when’, not ‘if’.

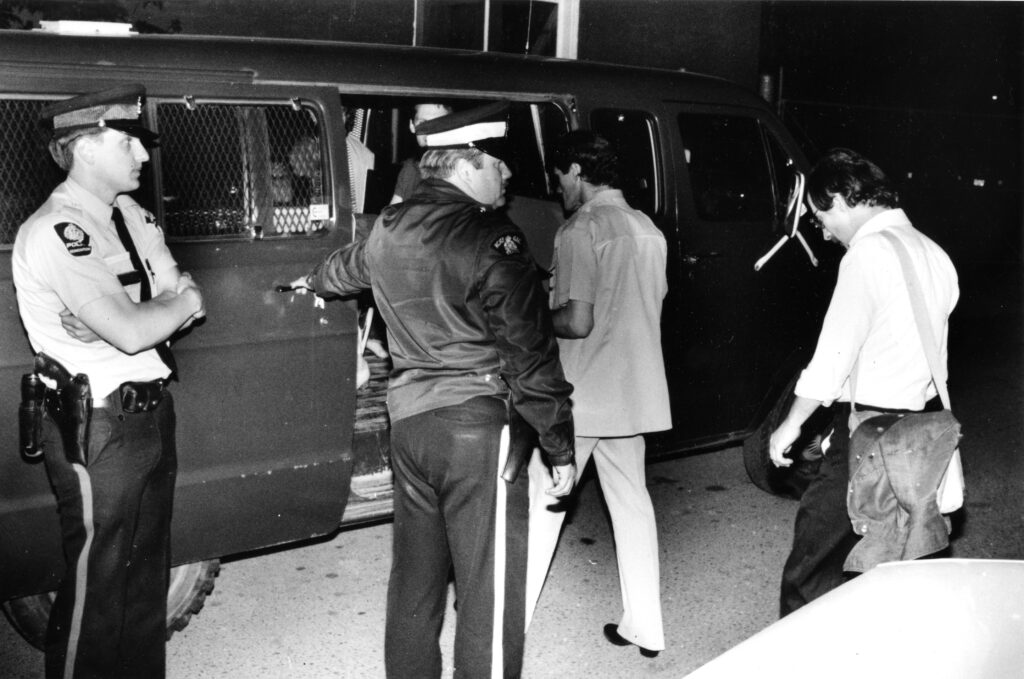

Evidently, the Pisces’ number came up on May 30, 1981. As detectives made their final undercover rounds, dozens of police officers and RCMP officers — answering to the dystopian-sounding Chief of the Morality Department — gathered nearby, ready to strike. At the signal, 40 Edmonton police officers and 12 RCMP officers stormed Pisces. The raid was swift and efficient, with officers sweeping through the bathhouse, kicking in doors, and rounding up patrons. Police and the Identification Department meticulously documented everything, photographing each man in whatever state they were found before allowing them to dress and taking another photograph with a sign bearing their personal information.

Unusually, not one but two Crown Prosecutors were present during the raid, supervising the arrests. The men were then taken to the courthouse for a still-unheard-of middle-of-the-night arraignment — no lawyers. By dawn, the 56 men charged as “found-ins” of a “common bawdy house” (there’s that term again) had been processed without access to legal counsel. At the same time, police arrested spa owner/financier Dr. Henri Toupin, his lover Eric Stein, and Kerr in their homes, charging them as the “keepers” of the bawdy house. “Items were seized from their bedrooms — items like poppers and Vaseline — as if proof was needed that they were gay.”

It can feel tough to conceptualize something like this happening today — even in our politically-fraught present, we as a queer community have places where we are allowed to gather without fear; we take our safe spaces where we can and fight for them tooth and nail, as best we can. The Pisces Raid is disturbing then, in its recency. We are increasingly finding our existence as queer people challenged yet again, politicized as always, even in a climate that is slowly dragging itself towards more visible forms of acceptance and inclusion. The gap in awareness of our too-recent past creates a disconnect between those who have lived through these formative events, those who have grown-up benefitting from the hard-fought, hard-won battles of previous generations, and the cisgender heterosexual populace that considers both subsets of the queer community immaterial.

Case in point, the contemporary media was perhaps too eager to cover the raid, with sensationalist headlines splashed across Edmonton’s news outlets the next morning. In an especially brazen, mean-spirited overreach, CFRN (now CTV) broadcasted the names of those arrested, causing a wave of outrage and fear throughout the community. The revelation that the police had, in fact, seized the spa’s complete membership list only deepened the anxiety, sparking concerns about potential charges against others who hadn’t been present during the raid; every single person involved with the spa — regardless of identity — were now functionally implicated. Ron Byers — a staffer — said he had planned to be at Pisces the night of the raid to celebrate a friend’s birthday, but ultimately requested time off — “That raid shattered lives, literally, because it wasn’t just gay people that were there. There were straight people there, there were people who were questioning their sexuality. There were people who, to this day, they still consider themselves straight,” said Byers3.

In the aftermath, Edmonton’s gay community came together in solidarity. Local gay bars, Flashback and The Roost, opened their doors for the arrested men to meet and organize their legal defense. Shelley Miller, a young lawyer, took on many of the found-ins, while the Gay Alliance Towards Equality (GATE) offered support and information to the community. Toupin, Stein, and Kerr ultimately pleaded guilty, fearing the scandal’s impact on their personal and professional lives, leading many found-ins to follow suit. This resulted in guilty pleas and fines, although future LGBTQ+ activist Michael Phair successfully appealed his case, receiving an unconditional discharge.

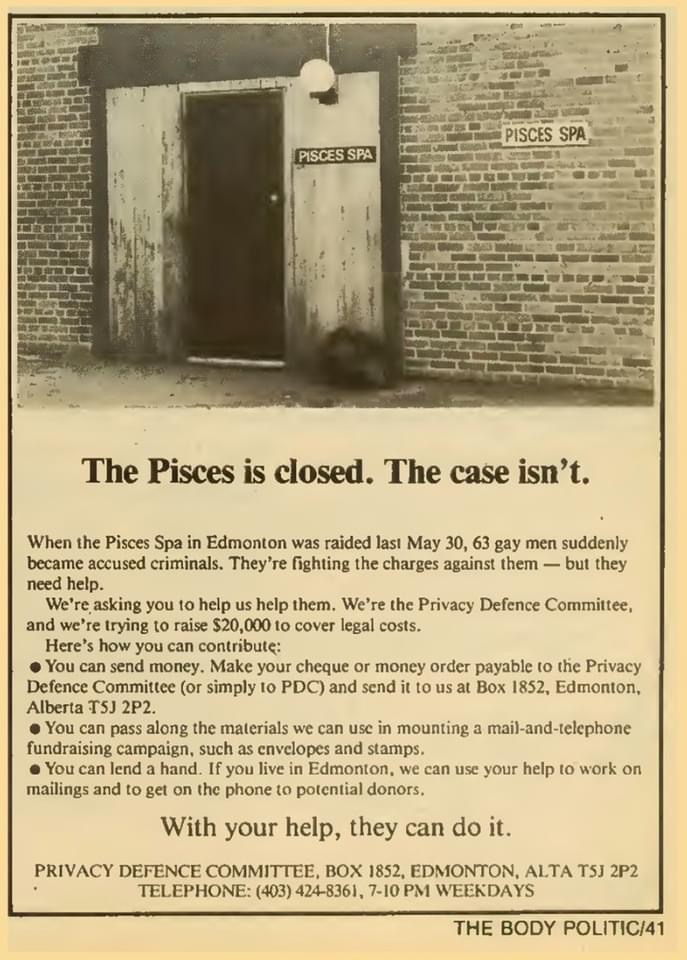

Despite the legal outcomes, the raid had a profound and lasting effect on Edmonton’s queer community. The police force’s overreach galvanized the community into action. Protests were organized, including one outside city hall, and the Privacy Defence Committee was formed to defend the rights of the arrested men. The S.S. Pisces 2, a cheeky protest raft in the annual Klondike Days Sourdough Raft Race complete with a pink triangle sail, symbolized the community’s refusal to be silenced; unflappable rebellion against the powers that be.

It would be four decades before any of said powers would try to disavow the 1981 raid. EPS did not formally acknowledge the harm they’d caused until 2019, when Edmonton police chief Dale McFee issued an apology to Edmonton’s LGBTQ community for — among other things — the raid. “To the members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer and two-spirit community — both across our public and within our service — on behalf of the Edmonton Police Service, I am sorry and we are sorry,” said McFee in the May 2019 apology. “Our actions caused pain. They eroded trust. They created fear.”

On the 40th Anniversary of the Pisces Bathhouse Raid, the Edmonton Police Service did a short documentary featuring LGBTQ+ activist Michael Phair, Queer Historian and researcher Darrin Hagen and former Pisces staff person Ron Byers (also founder of Rainbow Story Hub).

May 30, 2021 marked the 40th anniversary of the Pisces Health Spa bathhouse raids by the Edmonton Police Service (EPS). To acknowledge the trauma and impact of the raids, and to show our support to the Two-Spirit, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Transgender, and Queer (2SLGBTQ+) community, the EPS released a documentary-style video with commentary from local community members sharing their experiences and perspectives.

To view the video please go to this link:

https://www.edmontonpolice.ca/News/SuccessStories/PiscesHealthSpa40th

The fear, however, meant something. The raid on the Pisces Spa is now recognized as a pivotal moment in the history of LGBTQ+ activism in Edmonton. In the raid’s wake, Edmonton’s first Pride events were organized in 1982, evolving into Gay and Lesbian Awareness Week by 1984. It took over a decade for the first official Pride parade to occur, with participants donning bags over their heads to protect their identities. In 1993, Mayor Jan Reimer officially proclaimed Gay and Lesbian Pride Day, marking a significant milestone in the ongoing struggle for acceptance and equality.

The Pisces Bathhouse Raid ignited a new era of activism within Edmonton’s queer community and across Canada, challenging the complacency of the past and paving the way for future generations to fight fiercely for their rights. The raid was a dark day, but the activism that dawned shortly thereafter is still being felt to this day, and for that reason, it’s worth remembering; we have a responsibility to remember our past, or else there’s no chance of real generational unity.

Additional reading:

Chief Dale McFee delivered an apology to the LGBTQ2S+ Community. “The apology acknowledged that while police have an obligation to uphold the law and to create safe communities for everyone, the EPS has not always demonstrated behaviors and approaches which embody our core values. It is important for us to take this first step toward reconciliation and make amends with this important community.”

Aldynne Belmont

Aldynne H. Belmont is an American-Canadian lesbian, writer, lover of storytelling, and sometimes-showgirl, in that order. Aldynne has happily become entangled in the wide and wonderful web of YEG’s queer scene since moving to the city in 2020, and is a graduate of Edmonton’s own University of Alberta with a Bachelor’s in English and Film.

Her published work includes essays, journalism and theatre. Most recently, her stage play Ride Lyke Hell — described as a “lesbian friends-to-lovers romantic-comedy road-trip post-western” — debuted as a stand-out at Theatre Network’s Nextfest 2024.

She is both proud and absolutely giddy to be making a “serious, grown-up girl career” of the written word. Aldynne lives with her beautiful partner, two cats, and a very loud little dog in a townhouse designed by Wallbridge and Imrie.

Spread the word! Share this story now

55Shares

Advertisements