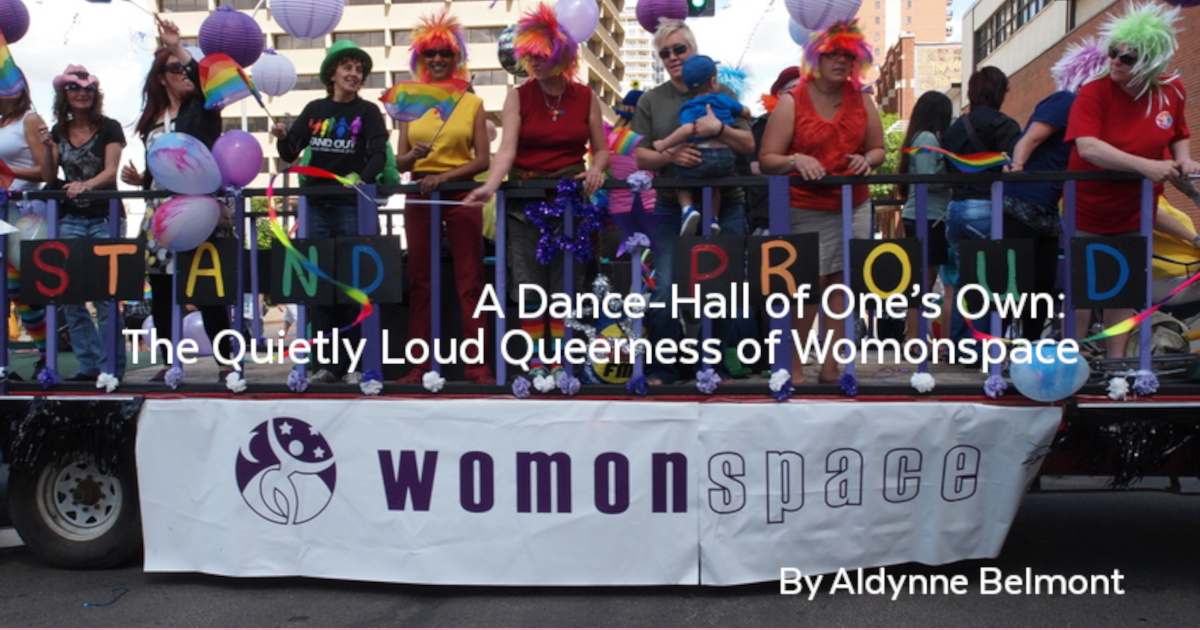

A Dance-Hall of One’s Own: The Quietly Loud Queerness of Womonspace

As a student of English (the language and literature) and a feminist, I always find it funny when lesbian and woman-focused organizations and titles try to censor the word ‘men’ — womyn, womun, womon, and the attempted (decidedly transphobic) subversion wombmen. The semiotics/etymology inherent to our understanding of ‘man’ as male vs. ‘man’ as mankind are kind baked-in, difficult to untangle. However, I don’t think the impulse to create something — to affirm an existence — completely independent of men and a male-dominated society is a bad one. In fact, it’s outright beautiful.

There’s no better example of that impulse than Womonspace — an organization with an almost 40-year run and a beautiful lasting legacy that is still observable today.

The year was 1981 — disco had come and gone, and queer women were still struggling to find places to let their hair down, shake off the day. Bars like Flashback and The Roost were throwing their doors open and bumping, but it was still, as the fella says, a man’s world. A city of women without a true “room of one’s own”, as Virginia Woolf once put it. A city of women lacking a space they felt true ownership of — a city of women without a place to dance, a place to breathe, a place to be.

Womonspace emerged as a response to the glaring lack of safe spaces where lesbians could socialize and participate in activities without facing judgment at best and outright discrimination at worst. Two women, Jeanne R. and Ann E., were inundated with complaints from the women they counseled at Gay Alliance Toward Equality (GATE) — concerns about the absence of a lesbian social scene — and decided to do something about it. Not with petitions or protests (those would come later), but a party. A big one — a dance, at Odd Fellows Hall, September 1981. No pretense, no politics. Just an opportunity for women to show up, drink something strong, and move their bodies to music.

The dance was a success, a glorious, sweaty hit. And suddenly, everyone knew it: Edmonton’s lesbians needed a space of their own. More than that, they needed an organization. Something with staying power. So, in January 1982, Jeanne, Ann, and a handful of others got together and formalized what would soon become Edmonton’s longest-running social, recreational, and educational society for lesbians. The volunteer-based org was christened Womonspace, and things were able to start in earnest. Womonspace was officially incorporated as a non-profit society in 1982, an important milestone that provided the group with a legal foundation to operate.

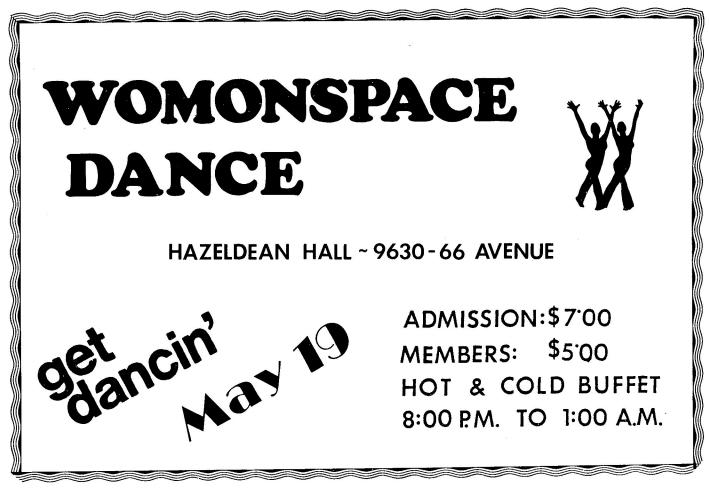

The early events were tailored to the needs and interests of the membership — dances, drop-ins. Whatever it took to get women out of their apartments and into spaces where they could meet each other without fear of being manhandled or sneered at. The events truly took off once they obtained a liquor license — no small feat back then — and suddenly the monthly dances became a staple of Edmonton’s nightlife. Hazeldean Hall (the location of Womonspace’s first official dance), Riverdale Hall, Bellevue Hall—wherever they could get a booking, they threw a party; the revenue generated by these early events was leveraged into financial independence from GATE, allowing Womonspace to organize their own dances, fundraisers, and social events without external financial support.

Over the years, Womonspace grew both in scope and significance. The organization itself became a beacon, with the events acting as a vital hub for the lesbian community in Edmonton and the surrounding areas. Among the many activities Womonspace organized were pool tournaments, golf outings, camping trips, self-defense classes, roller skating nights, and even safer-sex workshops in a time where such a thing was uncommon. I’m reminded of a line from the Coen Brothers film The Big Lebowski — “It’s a male myth about feminists that we hate sex. It [is] a natural, zesty enterprise.”

This is all to say that Womonspace facilitated a broad range of opportunities for lesbians to connect in different environments, all free from the judgment or exclusion they often encountered elsewhere. As one long-time member put it, Womonspace became “a place where women could be themselves without fear of being outed or harassed.” All of this wasn’t just a good time. This was a lifeline, a much-needed sense of solidarity and visibility in a world that often tried to erase queer women. Instead of small, private gatherings in people’s homes, these events allowed lesbians to gather in larger numbers, reinforcing a collective identity and showing that they were not alone in their experiences. A hundred, sometimes a hundred and fifty women crammed into a hall, laughing, dancing, and for once, not worrying about being alone in a city that didn’t even acknowledge they existed.

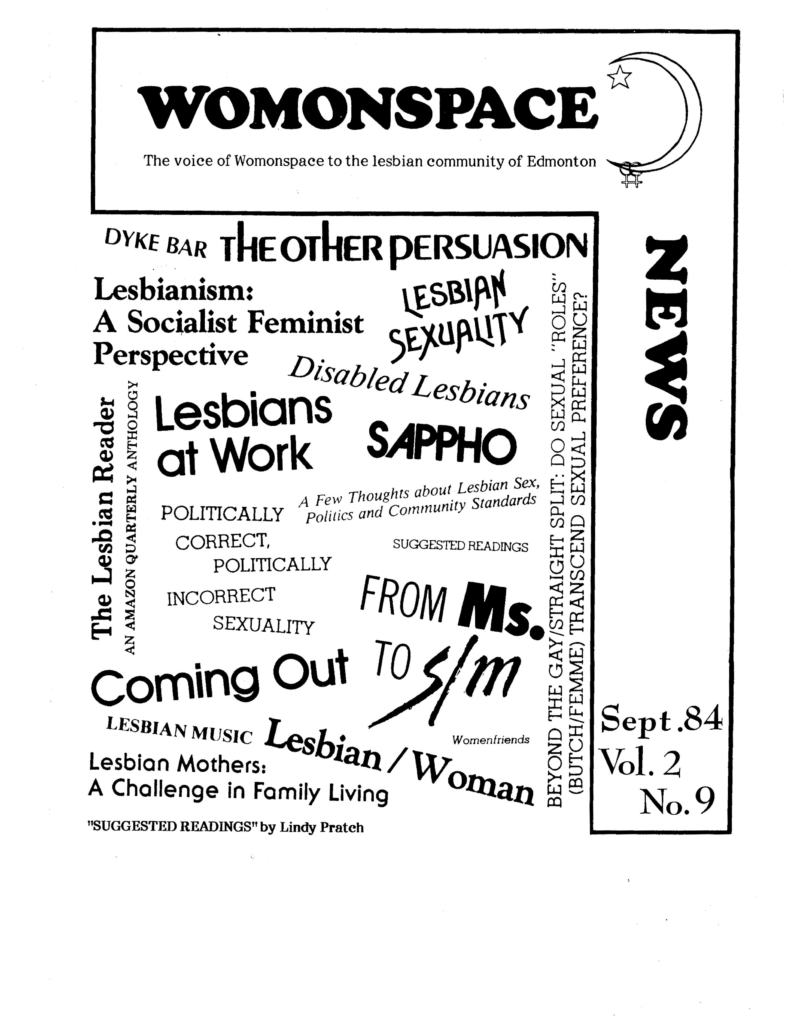

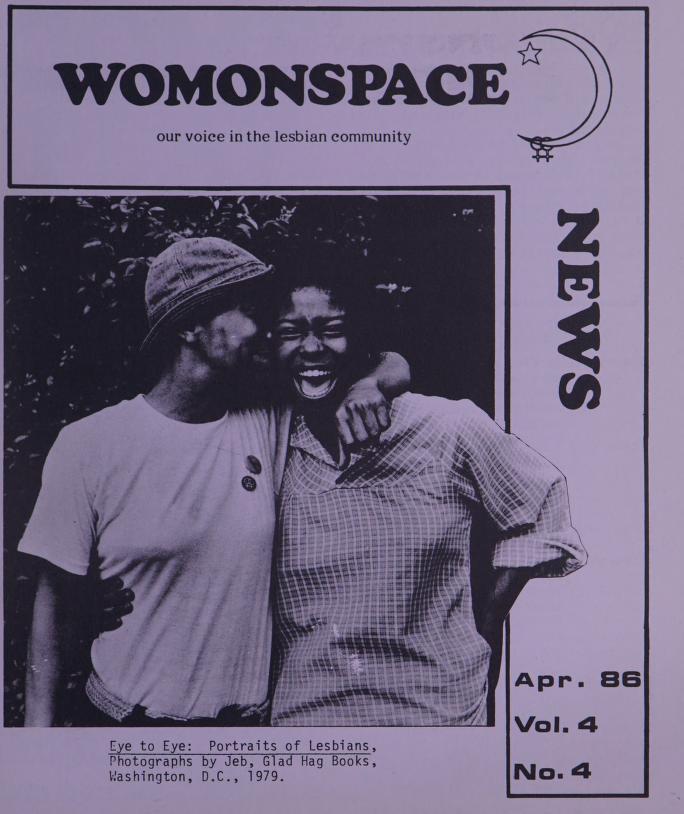

One of Womonspace’s most significant contributions to the community was its newsletter, Womonspace News. Launched in October 1982, the newsletter provided members with crucial information about upcoming events, community news, and resources. In the days before the Internet and social media, the newsletter was an invaluable communication tool, helping lesbians stay connected and informed. Copies were mailed in discreet envelopes to ensure privacy, a reflection of the high levels of stigma and fear that many lesbians faced at the time. Extra copies were also distributed in lesbian-friendly locations such as bookstores, coffee shops, and at dances.

Womonspace News did more than just promote events—it created a platform where women could share their thoughts, experiences, and creative work. The newsletter regularly featured poetry, book reviews, articles on lesbian spirituality, and personal essays on issues such as aging, coming out later in life, and living with disabilities. It became a forum for the exchange of ideas and a space where women could engage in discussions about the intersection of their identities, including their experiences as lesbians, feminists, and activists. In this sense, Womonspace functioned as what feminist theorist Nancy Fraser described as a “subaltern counterpublic,” providing a countercultural space for marginalized voices to share their needs and desires outside the dominant public sphere.

In those days, being a lesbian wasn’t exactly something you advertised. You could lose your job, your apartment, even your kids, if someone decided you were too much of a “risk.” The stakes were high, and Womonspace knew it. They played it smart — no protests, no big media splashes; it was an event network first. The point was to create a demonstrably safe tangible space, a place where women could let their guard down. If you wanted to come in, have a drink, and dance with someone without having to look over your shoulder, this was it.

However, not all discussions within Womonspace were without controversy. As the organization grew, so did the diversity of opinions within the community. Topics such as the role of feminism, pornography, and the oppression of trans and bisexual women were often hotly debated in the pages of Womonspace News, but also more direct local issues, like the inclusion of strippers at the dance events and the exact definition of “lesbianism” as it pertained to their organization. The publication was a platform for sharing poetry, stories, but also frustrations. Most of it was beautiful; some of it became increasingly messy.

Where feminist gather, you find thoughts and opinions; where opinions clash, you find internal friction. The organization’s leadership, wary of alienating its more closeted/discreet members, avoided overt political stances. Some felt this limited the group’s potential impact. Womonspace’s primary mission was to provide a safe, welcoming environment for its members, and political activism could, at times, jeopardize that mission. To exist as a lesbian — for your life to decentre men by definition — is inherently political, which of course opens you up to scrutiny.

One particularly notable conflict arose in the 1980s when two members, Liz Massiah and Jackie, were expelled from Womonspace due to their political activism. They had publicly challenged John Crosbie, Canada’s Minister of Justice, to amend the Human Rights Code to include protection for gays and lesbians. This public visibility clashed with Womonspace’s policy of discretion, as many members feared that such attention could lead to professional or personal repercussions. Liz reflected on the expulsion, stating that while Womonspace provided a much-needed safe space for women, it was often at the cost of political engagement. This tension between activism and safety was a defining feature of Womonspace’s history and echoed similar struggles within other 2SLGBTQ organizations at the time. The debates raged on — Should they be political or not? Could they keep Womonspace safe without alienating women who wanted more than just dances and drop-ins? These questions never fully went away. Even in the 1990s, when GALA (Gay and Lesbian Awareness) split into two departments — one side for politics, the other for social gatherings — the ghost of that argument haunted Womonspace.

Despite these challenges, Womonspace’s impact on Edmonton’s lesbian community was profound. For nearly four decades, it provided a consistent space for lesbians to gather, support one another, and navigate the complexities of their identities in a world that was often hostile to them. Its legacy is not just in the events it hosted or the newsletter it published but in the sense of community and belonging it fostered among countless women who, for the first time, felt they had a place to call their own.

By the time Womonspace held its final dance in 2018, the world had changed. Lesbian bars were now a damn sight fewer, but the internet had opened up an unprecedented level of interpersonal connection and communication, even and especially for queer people. Womonspace held its ground for 37 years — a quiet revolution in a noisy queer world — marking the end of an era for Edmonton’s 2SLGBTQ community. It was a ‘place’ that queer women willed into existence, sustained by the sweat and dedication of volunteers, thinkers, organizers who believed in its value.

Although the organization is no longer active, its influence can still be felt in the city’s queer spaces and the women who carry its history forward. It stands as a testament to the power of grassroots organizing and the importance of creating spaces where marginalized communities can not only survive but thrive. You would think a few women dancing in a community hall wouldn’t be enough to shake up a city, but it did. It was more than any one activity or branch — more than the sum of its parts. Womonspace was queer womanhood asserting “We’re here. We exist. You can’t ignore us forever.”

The Edmonton Queer History Project has compiled a collection of about 245 issues of the Womonspace News. To read them please go to the Edmonton Queer History Collection on Archive.org

Aldynne Belmont

Aldynne H. Belmont is an American-Canadian lesbian, writer, lover of storytelling, and sometimes-showgirl, in that order. Aldynne has happily become entangled in the wide and wonderful web of YEG’s queer scene since moving to the city in 2020, and is a graduate of Edmonton’s own University of Alberta with a Bachelor’s in English and Film.

Her published work includes essays, journalism and theatre. Most recently, her stage play Ride Lyke Hell — described as a “lesbian friends-to-lovers romantic-comedy road-trip post-western” — debuted as a stand-out at Theatre Network’s Nextfest 2024.

She is both proud and absolutely giddy to be making a “serious, grown-up girl career” of the written word. Aldynne lives with her beautiful partner, two cats, and a very loud little dog in a townhouse designed by Wallbridge and Imrie.

Spread the word! Share this story now

7Shares

Advertisements