A Brief Police History of Queer Edmonton

In a prior story, we covered the 1981 Pisces Bathhouse Raid — a defining moment in Edmonton’s 2SLGTBQ+ history/activism, but far from an isolated incident. The raid marked the breaking point for queer-police relations in the city; it was the inevitable result of a much larger pattern of harassment and moral panic that had shaped the lives of queer people in the province for decades.

The roots of this policing stretch back to the 1930s and 1940s, during the tenure of William “Bible Bill” Aberhart, who sat comfortably in Alberta’s premier chair from 1935 to 1943. Aberhart was a staunch social conservative who believed in maintaining a strict moral code that bordered on Puritanism. His Social Credit government laid the legal foundations for decades of brutal systemic and interpersonal harassment—policies designed to maintain the moral fabric and “public decency” with exactly zero subtlety.

These policies were made with precedent — laws like the 1890 criminalization of sexual activity between men under Canada’s gross indecency law were already used by police to target gay men for decades.

One of the most infamous early examples of this persecution occurred in 1942 with a series of same-sex trials in Edmonton. The trials were the result of a coordinated effort between the RCMP and Edmonton Police, who conducted a sting operation in response to a personal ad in the Edmonton Journal. Over the course of a few months, ten men were arrested, and nine were convicted for engaging in same-sex activity.

The trials drew media attention, with newspapers sensationalizing the story and portraying the men as part of a depraved “ring of bestiality” operating under the noses of polite Edmonton society. Homophobia in the legal system and press was standard, a symptom of the existing public discourse around queer people.

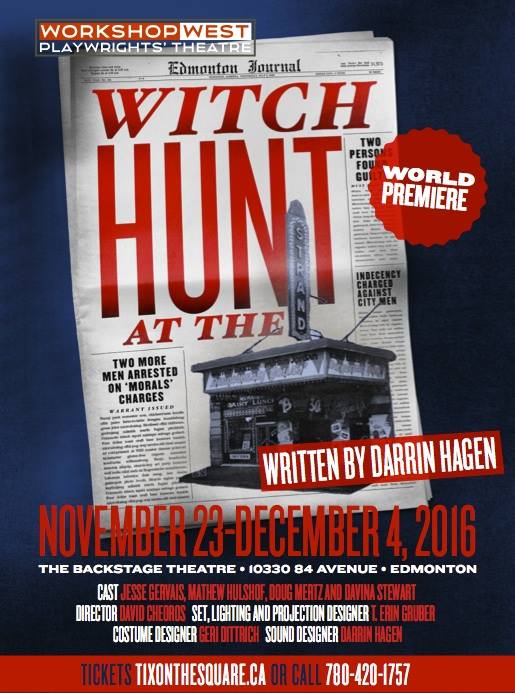

Darrin Hagen’s Witch Hunt at the Strand tells the story of the Same-Sex Trials of 1942 where 10 men who gathered at the Strand Theatre on Jasper Avenue were charged for same-sex activities.

Witch Hunt at the Strand was first presented August 14 – August 23, 2015 at the Edmonton International Fringe Festival and had its World Premiere November 23 – December 4, 2016 by Workshop West Productions at the Backstage Theatre.

Private spaces weren’t safe either. Even behind closed doors, queer people in Edmonton risked arrest and public humiliation. In 1955, for example, two men were arrested for engaging in consensual same-sex relations in a private home after a neighbor reported hearing them. The men were charged and socially vilified, victims of a pervasive moral policing culture.

Even after the 1969 federal decriminalization of same-sex relations in Canada, it was open season for law enforcement well into the 70s and 80s. The public display of queerness was seen as an affront, something to be crushed, even with the emergence of organizations like GATE (Gay Alliance Towards Equality) and spaces like Club 70. The cops kept tabs on who came and went from gay bars, who was kissing who, always ready to pounce. In 1977, two men were arrested in Queen Elizabeth Park for daring to kiss in a parked car. While in custody, they were subjected to homophobic slurs and threats from police officers, who even informed their employers of the incident. Despite their employers’ indifference, the men’s experience underscored the vulnerability of 2SLGTBQ+ people to both legal persecution and public shaming. Police showed little interest in protecting the community from anti-gay violence; incidents of gay-bashing and violence against male sex workers increased, particularly in cruising areas like “The Hill” near Alberta College, yet the police took limited, if any, action.

By the 1980s, police raids on gay bathhouses had become a common occurrence across Canada. In cities like Montreal and Toronto, authorities targeted these spaces under the guise of enforcing morality laws. Edmonton would face its own reckoning with the infamous Pisces raid in 1981, which you can read about in full here. The raid was heavily criticized for its aggressive tactics, including invasive surveillance, humiliation of those arrested and a draconian denial of legal counsel. Defense lawyer Sheila Greckol argued that the police disregarded the rights of the men, many of whom were forced to endure humiliating treatment during and after the raid.

There was no Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms yet to protect these men. When the Charter came the next year, Anne McLellan — Associate Dean of Law at the University of Alberta — pointed out, it didn’t include protections for gays and lesbians, and essentially failed to challenge the state’s license to persecute queer people.

The Pisces raid sparked outrage, with Philip Knight of the Privacy Defense Committee questioning the police’s motives. Rather than protecting the public, the raid seemed to serve no purpose beyond instilling fear and anger in the 2SLGTBQ+ community.

Paradoxically, the raid had an unintended effect: it galvanized the 2SLGTBQ+ community in Edmonton. The queer community had already been organizing, slowly building momentum — visibility, protest, voice — throughout the ’70s, but the Pisces raid lit the fuse. Suddenly, there was fire. There was anger. There was action. Organizations like GALA (Gay and Lesbian Awareness) and Dignity Edmonton — groups that played crucial roles in advocating for 2SLGTBQ+ rights and providing support during the AIDS crisis — emerged in the aftermath of the raid. The backlash also led to a broader push for police accountability.

By the early 1990s, relations between the Edmonton Police Service and the 2SLGTBQ+ community began to shift. In 1992, GALA’s activism led to the creation of the Gay and Lesbian Liaison Committee, one of the first of its kind in Canada. The committee, made up of police officers and 2SLGTBQ+ representatives, aimed to improve communication and address systemic discrimination — an attempt at diplomacy, a proposed ceasefire. Its formation marked a significant step toward reconciliation, but police harassment continued. That same year, while the committee was shaking hands and signing agreements, undercover sting operations in Victoria and Government House parks led to the arrest of several gay men for consensual sex acts, reigniting tensions between the community and law enforcement.

It would be dismissive of the real change wrought by the Liaison Committee to refer to the whole experiment as a PR initiative; they laid the groundwork for positive change and forced the Edmonton Police Service to address the justifiable tensions and long history of harm. By the late 1990s, the Edmonton Police Service launched an anti-gay bashing campaign, with posters that boldly declared, “Being gay is not a crime. Gay-bashing is.” This campaign, supported by the Liaison Committee, was an important step in raising awareness about violence against 2SLGTBQ+ people and encouraging victims to come forward. The police also began participating in Pride events, symbolizing a new era of cooperation; the bold words needed to be backed with action.

However, this relationship would later come under scrutiny. By 2017, amid growing concerns about the role of law enforcement in 2SLGTBQ+ spaces, uniformed police officers were banned from Toronto’s Pride parade. Edmonton followed suit in 2018, with the police voluntarily withdrawing from the parade in response to community feedback. The following year, the Pride parade was canceled altogether due to broader tensions over corporate interests/involvement and the exclusion of marginalized groups within the 2SLGTBQ+ community.

Today, the former Sexual and Gender Minorities Community Liaison Committee continues to work toward building trust between the Edmonton Police and the 2SLGTBQ+ community under a new name and structure as the Sexual Orientation Gender Identity and Expression (SOGIE) Advisory Council. While there has been significant progress, the legacy of past persecution serves as a reminder of the importance of vigilance, dialogue, and continued advocacy for true equality. We, as a community, are still trying to bridge the gap between memories of brutal repression and a police force attempting to rewrite its own narrative.

For additional reading:

Raid on Pisces Bathhouse — Darkest Before the Dawn

Liz Massiah – Edmonton’s Lesbian Community Leader Extraordinaire

Murray Billett – Advocate Educator Activist

Murray Billett served as Chair and Vice Chair during his time as the first openly gay member of the Police Commission from 2004 – 2009

A Damn Proud Gay Canadian Soldier – Part One

A Damn Proud Gay Canadian Soldier – Part Two

In these two video interviews former member/Chair of the Edmonton Police Commission – Murray Billett interviews recently retired Chair – John McDougall

Aldynne Belmont

Aldynne H. Belmont is an American-Canadian lesbian, writer, lover of storytelling, and sometimes-showgirl, in that order. Aldynne has happily become entangled in the wide and wonderful web of YEG’s queer scene since moving to the city in 2020, and is a graduate of Edmonton’s own University of Alberta with a Bachelor’s in English and Film.

Her published work includes essays, journalism and theatre. Most recently, her stage play Ride Lyke Hell — described as a “lesbian friends-to-lovers romantic-comedy road-trip post-western” — debuted as a stand-out at Theatre Network’s Nextfest 2024.

She is both proud and absolutely giddy to be making a “serious, grown-up girl career” of the written word. Aldynne lives with her beautiful partner, two cats, and a very loud little dog in a townhouse designed by Wallbridge and Imrie.

Spread the word! Share this story now

10Shares

Advertisements